It's been a while since my last post. I took some time off from blogging during the holidays, and lost all momentum I had when I got back. Hopefully I will get back to posting regularly.

For the first post of the new year I decided to write a rudimentary introduction to reading kuzushiji (崩し字). Although I am definitely no expert on the subject, I had to learn it myself from scratch when writing my master thesis, so I think I might have some valuable tips for the absolute beginner.

For the first post of the new year I decided to write a rudimentary introduction to reading kuzushiji (崩し字). Although I am definitely no expert on the subject, I had to learn it myself from scratch when writing my master thesis, so I think I might have some valuable tips for the absolute beginner.

Kuzushiji?

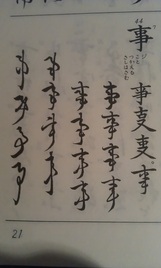

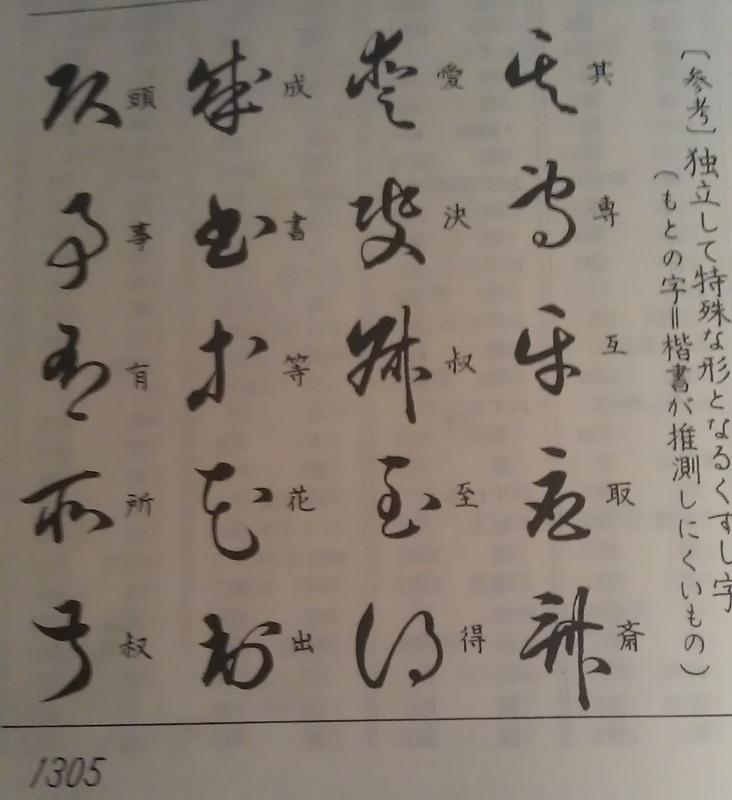

So what are kuzushiji anyway? Basically they are characters written in cursive style. As an example I have provided an image showing various degrees of cursive "degeneration" of the character 事. The image is from the dictionary くずし字用例辞典. As you can see, the examples included in the dictionary range from recognizable to difficult to downright impossible. It might look like a daunting task to learn how to recognize such characters, but characters such as 事 is so frequent that you will soon forget how impossible it once seemed. Typically, the more frequently a character is written, the more broken down it becomes. Below are some other examples of "impossible" characters.

So what are kuzushiji anyway? Basically they are characters written in cursive style. As an example I have provided an image showing various degrees of cursive "degeneration" of the character 事. The image is from the dictionary くずし字用例辞典. As you can see, the examples included in the dictionary range from recognizable to difficult to downright impossible. It might look like a daunting task to learn how to recognize such characters, but characters such as 事 is so frequent that you will soon forget how impossible it once seemed. Typically, the more frequently a character is written, the more broken down it becomes. Below are some other examples of "impossible" characters.

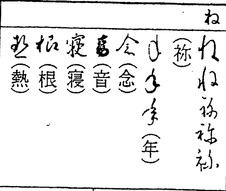

When reading kuzushiji you will encounter both kanji and kana. Just as when you started out learning Japanese, it is advisable that you start out with getting a grasp of the kana first. This is especially practical when looking at texts where there are a lot of furigana, making it easier to guess at which kanji are used. The difference between premodern and modern kana is that before Meiji, each syllable could be depicted in a variety of different ways. For instance, as you can see from the image to the right, the syllable ね could be written in seven different ways. Click on the link below to see the cursive renditions of other kana.

| kuzushikana.pdf |

Tools of the trade

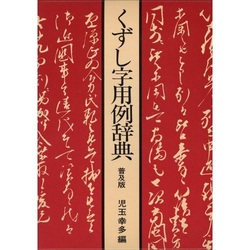

To start out with kuzushiji you're going to need a good dictionary. Basically, there are two kinds of dictionaries. One you use when you have absolutely no clue at which character you're looking at and one for when you have one or several reasonable guesses. The first one works in such a way that you look for characters in such a way that you guess at which stroke is the first stroke in the character, and move on from there. For instance, if you think the first stroke of the character you're looking at is a straight downward stroke, there is a whole section in the dictionary that collects such characters. An example of such a dictionary is the くずし字解読辞典.

The other method is, in my mind, much more useful and I have personally used this the most. By looking at the context of the text you are reading, and also by looking at the general shape of the character you are struggling with, most of the time you will have one or several reasonable guesses at which character it is. So if you, for instance, think you are looking at 事 you would find the character in the dictionary and confirm or deny your guess. If it was wrong, repeat the process for your next guess. An example of such a dictionary is the くずし字用例辞典 which is pictured above. This dictionary is also ordered by radicals, so if you recognize only the radical of a character you can easily browse the radical section for it.

There's also a convenient online database for looking up characters at http://clioz39.hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ships/ZClient/W34/. Unfortunately it is currently only possible to search for one character at the time, so you cannot search for compounds. It might, however, be quicker than manually looking up a character in the dictionary.

To start out with kuzushiji you're going to need a good dictionary. Basically, there are two kinds of dictionaries. One you use when you have absolutely no clue at which character you're looking at and one for when you have one or several reasonable guesses. The first one works in such a way that you look for characters in such a way that you guess at which stroke is the first stroke in the character, and move on from there. For instance, if you think the first stroke of the character you're looking at is a straight downward stroke, there is a whole section in the dictionary that collects such characters. An example of such a dictionary is the くずし字解読辞典.

The other method is, in my mind, much more useful and I have personally used this the most. By looking at the context of the text you are reading, and also by looking at the general shape of the character you are struggling with, most of the time you will have one or several reasonable guesses at which character it is. So if you, for instance, think you are looking at 事 you would find the character in the dictionary and confirm or deny your guess. If it was wrong, repeat the process for your next guess. An example of such a dictionary is the くずし字用例辞典 which is pictured above. This dictionary is also ordered by radicals, so if you recognize only the radical of a character you can easily browse the radical section for it.

There's also a convenient online database for looking up characters at http://clioz39.hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ships/ZClient/W34/. Unfortunately it is currently only possible to search for one character at the time, so you cannot search for compounds. It might, however, be quicker than manually looking up a character in the dictionary.

An example

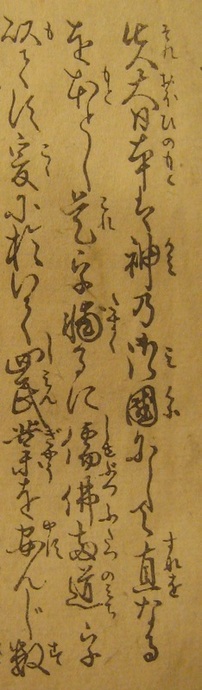

Let's look at some actual text. This excerpt is from the introduction to the 永代節用無尽蔵. It was the first text I laid my hands on, and I think it was a good start because there are furigana. The furigana for the first four kanji reads それおいひのもと. Notice that the last two kana are different than the modern hiragana? Go to your dictionary or the pdf included above to see if you can find out which kanji they are derived from.

The next kana is also a new one. Can you guess which one from the context? Yes, it's は, derived from the character 者. This one is quite frequent in Edo-period texts, so remembering it is not much of a problem. Then you see the character 神, so you should be able to guess the furigana. Next up is の, before 御国(みくに). You see that the み looks like katakana ミ and that the に almost looks like ふ. Then the same に appears again before して. Next you see the character 直 with the furigana saying すなを. Notice that the な resembles れ and that を is used instead of お. The next kana reads なるを, before the character 本 with the furigana もと. The following kana reads とし. I don't know what the next kanji is, but the furigana says これ. Next we encounter a new kana, which is を. The next kanji is 補, with the furigana たすく with the following verb ending る. Next up is に before the four characters 儒佛両道. I am not quite sure about the second kana, but would guess the furigana says しゆぶつふたつのみち. The third character here, 両, i really struggled with for hours. Then we have を again, before the kanji 以 with the furigana も. Then there are two more new kana, which are て and す. This is a verb ending in shushukei, which means that it is the end of the sentence and therefore a nice place to stop. This then gives us the following reading of the text:

それ大日本(おいひのもと)は神(かみ)の御国(みくに)にして直(すなを)なるを本(もと)とし、これを補(たすく)るに儒佛両道(しゆぶつふたつのみち)を以(も)てす。

Let's look at some actual text. This excerpt is from the introduction to the 永代節用無尽蔵. It was the first text I laid my hands on, and I think it was a good start because there are furigana. The furigana for the first four kanji reads それおいひのもと. Notice that the last two kana are different than the modern hiragana? Go to your dictionary or the pdf included above to see if you can find out which kanji they are derived from.

The next kana is also a new one. Can you guess which one from the context? Yes, it's は, derived from the character 者. This one is quite frequent in Edo-period texts, so remembering it is not much of a problem. Then you see the character 神, so you should be able to guess the furigana. Next up is の, before 御国(みくに). You see that the み looks like katakana ミ and that the に almost looks like ふ. Then the same に appears again before して. Next you see the character 直 with the furigana saying すなを. Notice that the な resembles れ and that を is used instead of お. The next kana reads なるを, before the character 本 with the furigana もと. The following kana reads とし. I don't know what the next kanji is, but the furigana says これ. Next we encounter a new kana, which is を. The next kanji is 補, with the furigana たすく with the following verb ending る. Next up is に before the four characters 儒佛両道. I am not quite sure about the second kana, but would guess the furigana says しゆぶつふたつのみち. The third character here, 両, i really struggled with for hours. Then we have を again, before the kanji 以 with the furigana も. Then there are two more new kana, which are て and す. This is a verb ending in shushukei, which means that it is the end of the sentence and therefore a nice place to stop. This then gives us the following reading of the text:

それ大日本(おいひのもと)は神(かみ)の御国(みくに)にして直(すなを)なるを本(もと)とし、これを補(たすく)るに儒佛両道(しゆぶつふたつのみち)を以(も)てす。

What now?

There's really just only one way to learn how to read kuzushiji, and that is to get your hands dirty. Go find some texts and just try. It will be quite difficult at first, but as most other things it will get easier as you get used to it. You have to be quite patient though, as you will spend hours on what seems as quite little text, especially in the beginning. If there's a character you are struggling too much with, just skip it and continue ahead. It is likely that you will encounter the same character again later in the text, at which point you might be able to guess the meaning from the context more easily. I like to compare reading kuzushiji to solving sudoku or crossword puzzles. It is quite hard, sometimes impossible, to start in one end and expect to be able to solve everything going in a straight line. Skip back and forth and the pieces will eventually come together.

Go check out your university library and see if they have some texts that you can work with. It is quite rewarding to work with actual books instead of digital copies. If they don't have anything or if you don't find out anything, there are plenty of material online for you to get started. My personal favorite source is Waseda's 古典籍総合データベース where you will find many interesting sources in great quality downloadable as pdf. Check for instance out one of their copies of Heike Monogatari 平家物語 or a copy of the Tokaido Meisho Zue 東海道名所図絵. Good luck!

There's really just only one way to learn how to read kuzushiji, and that is to get your hands dirty. Go find some texts and just try. It will be quite difficult at first, but as most other things it will get easier as you get used to it. You have to be quite patient though, as you will spend hours on what seems as quite little text, especially in the beginning. If there's a character you are struggling too much with, just skip it and continue ahead. It is likely that you will encounter the same character again later in the text, at which point you might be able to guess the meaning from the context more easily. I like to compare reading kuzushiji to solving sudoku or crossword puzzles. It is quite hard, sometimes impossible, to start in one end and expect to be able to solve everything going in a straight line. Skip back and forth and the pieces will eventually come together.

Go check out your university library and see if they have some texts that you can work with. It is quite rewarding to work with actual books instead of digital copies. If they don't have anything or if you don't find out anything, there are plenty of material online for you to get started. My personal favorite source is Waseda's 古典籍総合データベース where you will find many interesting sources in great quality downloadable as pdf. Check for instance out one of their copies of Heike Monogatari 平家物語 or a copy of the Tokaido Meisho Zue 東海道名所図絵. Good luck!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed